Windows Registry Forensics: System vs. User Hives

Breaking down what the registry hives are, where they live, and why they’re essential in Windows forensics.

Introduction

After walking through NTFS in my last post, I want to shift gears into another cornerstone of Windows forensics which is the REGISTRY. The registry is essentially the brain of the operating system, storing both system-level configuration and user specific activity. For me, digging into registry hives is one of the fastest ways to understand how a machine was set up, what users were doing, and even how attackers tried to persist.

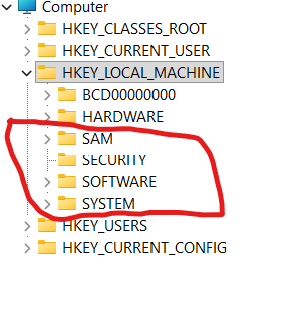

System Hives

HKLM\SAM — Stores local account information, including user and group details. Forensic gold when I need to map local accounts and their relationships.

HKLM\Security — Holds security info such as audit policies and security identifiers (SIDs). Useful for understanding how the system enforces security.

HKLM\System — Contains configuration data for attached hardware devices and system services. This hive helps me see how the system was set up and what hardware was in play.

HKLM\Software — Tracks installed applications, including Windows components themselves. Whenever I want to prove what was installed or configured on a machine, this hive is my first stop.

User Hives

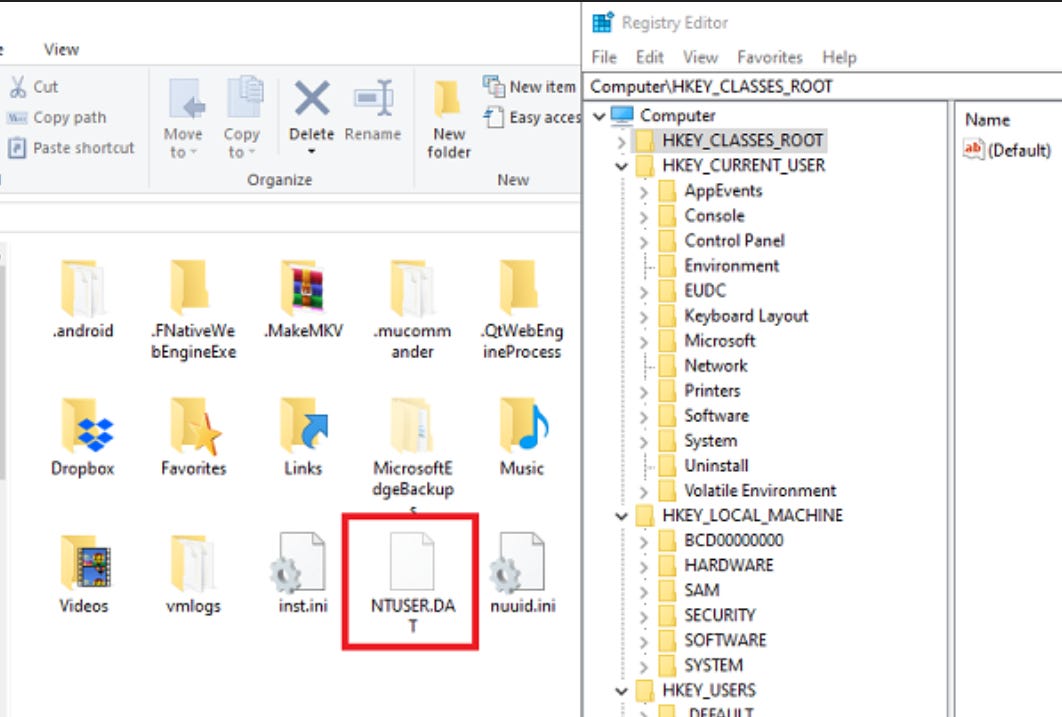

Each user account also has its own hive, which lives under HKEY_CURRENT_USER (HKCU) in live analysis. These are where I look to understand user specific behavior. In live analysis, we can browse the HKCU using the reggedit.exe, but most of the forensics analysis are offline which the user hive file will be NTUSER.dat and UsrClass.dat. In offline analysis, the best tool to use from my opinion is Registry Explorer because it’s user friendly and has a lot of plugins that could be used to parse the data available in human readable format.

NTUSER.dat — Located at

C:\Users\<username>\NTUSER.dat. This file records user-level settings, recent documents, application activity, and more.UsrClass.dat — Found at

C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\UsrClass.dat. This complements NTUSER.dat with additional user configuration and COM class information.

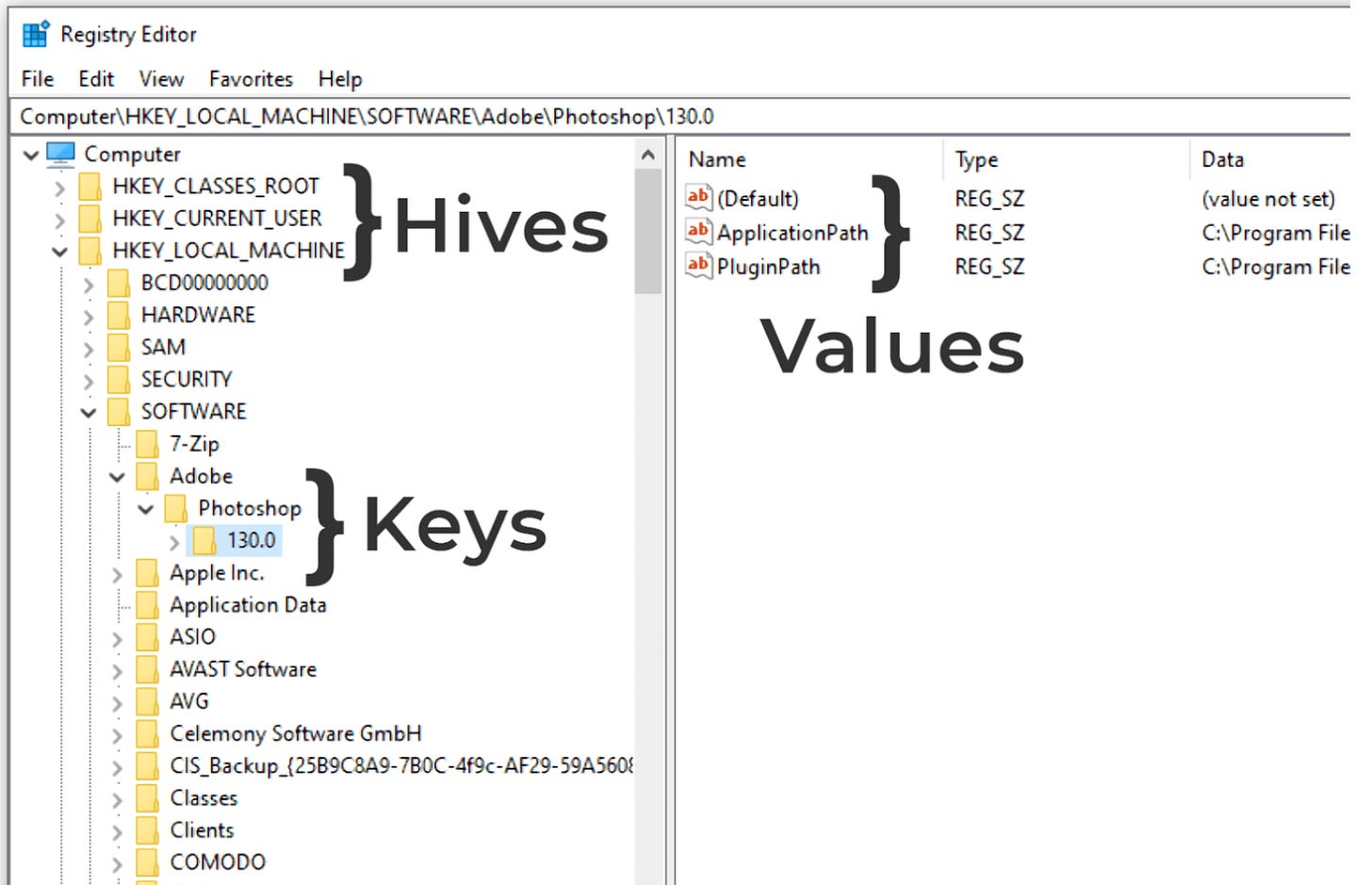

Registry Structure

The Windows Registry is organized like a hierarchical database with three main parts: hives, keys, and values. Hives, such as HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE or HKEY_CURRENT_USER, are the root containers that hold broad categories of system or user data. Within each hive are keys, which act like folders and group related settings together. For example, software entries under HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE. Keys contain values, which store the actual data, each with a name, a type, and content, like file paths or configuration details. Forensically, this matters because the registry records everything from installed applications to user activity and autostart entries attackers abuse for persistence, and each key maintains a Last Write Time that helps build timelines of system changes.

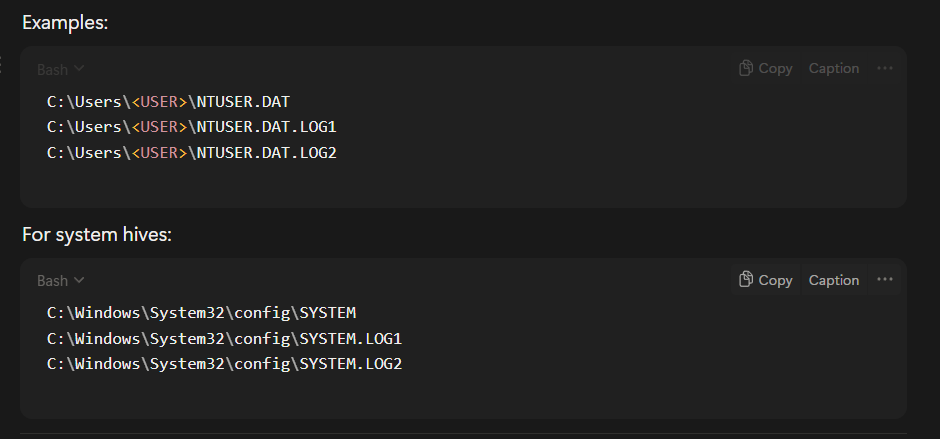

Registry Hives Transaction Logs

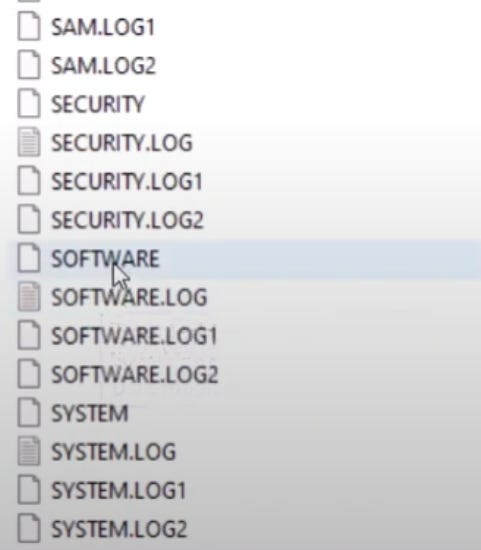

The Windows registry is a database, and like any database, it needs protection from corruption if the system crashes mid-write. To handle this, Windows uses transaction logs, which make registry updates atomiceither fully applied or not applied at all. These logs act like a safety journal, recording changes before they’re committed to the main hive. On disk, each registry hive file, such as NTUSER.DAT, SYSTEM, or SOFTWARE, is often accompanied by .LOG1 and .LOG2 files in the same folder—for example, C:\Users\<USER>\NTUSER.DAT.LOG1 and .LOG2, or C:\Windows\System32\config\SYSTEM.LOG1 and .LOG2. When a change occurs, Windows first writes the update to the log, then applies it to the hive itself; if something goes wrong, the system can replay the log on reboot to keep the registry consistent. The use of two logs in a circular pattern increases reliability in crash recovery.

For forensics, these transaction logs are highly valuable. They may contain deleted or short lived entries that never made it into the hive, they can reveal the last attempted changes before a power loss, and they allow investigators to reconstruct a timeline of registry modifications with greater detail. By analyzing these logs, I can sometimes catch evidence of user actions or attacker persistence that would otherwise be invisible once the registry hive is cleaned up.

Registry Explorer

Registry Explorer is my go-to tool for registry analysis because it makes navigating complex hives straightforward and efficient. Unlike regedit, it’s designed for forensics: I can load offline hives, search across keys, view last write times, and even bookmark important entries during an investigation. What makes it even better is its plugin capability with the built in plugins, I can quickly parse common forensic artifacts like user assist, shellbags, MRUs, and more without manually hunting through raw keys. This combination of ease of use, speed, and extensibility is why Registry Explorer is one of the best tools for registry forensics. Here is a video from SANS DFIR explaining this tool Video.

Eric Zimmerman has made the best open source tools until now and his tools are all listed in that link. Tools

Conclusion

The Windows registry is one of the richest sources of evidence in digital forensics, with system hives giving me insight into how the machine is configured and user hives revealing personal activity and behavior. Tools like Registry Explorer make parsing these hives far more practical, especially with its plugin support for common forensic artifacts. In this post, I wanted to set the foundation by introducing the main system and user hives, but in upcoming blogs I’ll go deeper into the individual keys inside each hive and show how they can be applied in real forensic investigations to uncover persistence, track user actions, and reconstruct timelines.